Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, USN (1884-1941)

Today is the 70th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. On that day, 19 American ships were damaged or sunk; 171 airplanes destroyed; 1,178 people injured; 2,389 killed; and 14 Medals of Honor awarded. Pearl Harbor memorials to those who died tend to list the names in alphabetical order. This is especially significant because one of the names is Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, Commander of Battleship Division One. The highest ranking casualty of the attack, he was the first U.S. Navy flag officer killed in action against a foreign enemy. The USS Arizona was his flagship.

In the early 20th Century, the Pearl Harbor memorial would have been a larger than life statue of Rear Admiral Kidd, probably not on a horse because he was a Navy man. We started seeing lists of names during World War I, with its massive losses and better record keeping. In that war, Rear Admiral Kidd would have been at the top of a hierarchical list of names. But in 1962, when her memorial was dedicated, the names from the USS Arizona were carved in alphabetical order, signifying equality of service. Rear Admiral Kidd is almost exactly in the middle, surrounded by his men.

Anchor of the USS Arizona on display at Wesley Bolin Memorial Plaza, Phoenix, AZ.

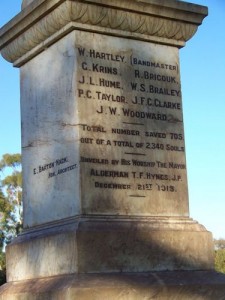

In Hawaii, Pearl Harbor or World War II memorials with names include the USS Arizona, USS Oklahoma, USS Utah, the Valor in the Pacific Remembrance Circle, and the Honolulu Memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. In Phoenix, the Arizona’s anchor sits atop a base displaying the names of her dead. The only exception to alphabetical order is the list of Arizona survivors who choose to be buried in the submerged ship. These names are located near their shipmates on the Hawaii memorial, but for practical reasons, they are chronological.

Rear Admiral Kidd among His Men at the USS Arizona Anchor Memorial in Phoenix

The Arizona accounts for almost half the deaths from the attack. She remains in the harbor, her superstructure removed and her hull visible under water. Most of the bodies were not recovered and are considered buried at sea. The USS Arizona Memorial, designed by architect Alfred Preis, straddles the mid-section of the ship without touching it. An open air building, reminiscent of a covered bridge, it is high on both ends and shorter in the middle, to symbolize December 7 as a low point from which America recovered.

USS Arizona Memorial

At the far end of the memorial is a wall with the 1,177 alphabetized names of those who died on the ship. Listings include initials, last name, and rank. Most are Navy, with 73 Marines in a separate section. Rear Admiral Kidd and the ship’s captain, Franklin Van Valkenburgh, have an extra line indicating their position in the ship’s command.

Both earned Medals of Honor, as did Lieutenant Commander Samuel G. Fuqua, who became the ship’s highest ranking officer during the attack. When personnel abandoned ship, he made sure everyone who could evacuate did so and he was the last person off. Many survivors credited him with saving their lives. About 90% of those on board at the time of the attack died. Today, when ships pass the memorial in the harbor, sailors honor the Arizona by manning the rails, standing evenly spaced along their ship’s railing.

USS Oklahoma Memorial

Don Beck’s 2007 memorial for the USS Oklahoma overlooks the harbor. Here the 429 alphabetized names are engraved on separate pillars, with the group of pillars fronted on two sides by short marble walls containing engraved quotes about Pearl Harbor. The visual effect is that of a ship with its sailors manning the rails to honor those who died. Two men from the Oklahoma earned Medals of Honor. Ensign Francis C. Flaherty and Seaman First Class James R. Ward both held lights in different turrets so the crew could escape. They did not survive when the ship rolled over. The Oklahoma was eventually salvaged but sunk while being towed to San Francisco for scrap metal.

USS Utah Memorial (with her exposed hull on the left)

The USS Utah is its own memorial, remaining in the harbor rolled over with its hull exposed. There are several plaques on a pier overlooking the wreck. One contains the names of the 58 who died including Medal of Honor winner Peter Tomich, the Utah’s Chief Watertender and a Croatian immigrant. His citation reads, “Although realizing that the ship was capsizing, as a result of enemy bombing and torpedoing, Tomich remained at his post in the engineering plant of the U.S.S. Utah, until he saw that all boilers were secured and all fireroom personnel had left their stations, and by so doing lost his own life.”

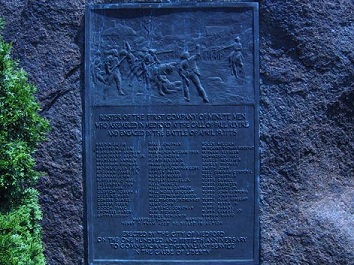

USS Arizona Memorial Visitors Center - Remembrance Circle

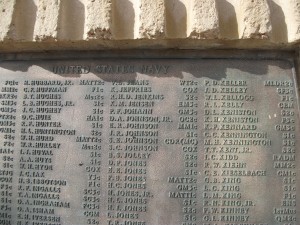

Also overlooking the harbor is the Remembrance Circle at the Visitor’s Center of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument, containing the names of all who died at Pearl Harbor, except those from the Arizona. Here the names are essentially organized by location, although military personnel are initially divided into their respective branches. Within each grouping the names are alphabetical. Based on this photo of an summary plaque, the branches are organized by Department of Defense order of precedence: Army, Marines, Navy. Today the Air Force would be in fourth place, but at the time it was part of the Army. Because of the overwhelming majority of Navy deaths, order of precedence continues to evoke equality. Note also that civilians are first. At the 1925 memorial to the Revolutionary War Minute Men in Medford, MA, a civilian who died is placed last.

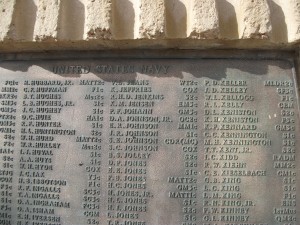

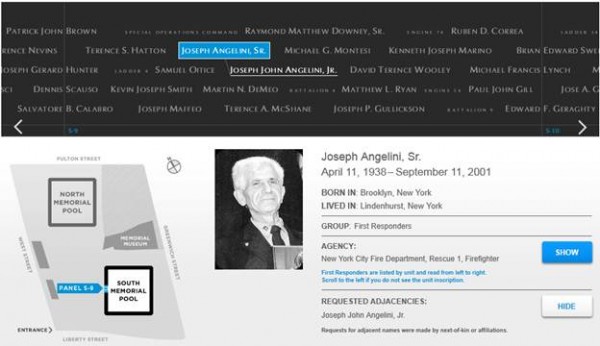

Located in the Punchbowl area of Oahu, the Honolulu Memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific consists of a wide staircase leading to a Liberty statue with Courts of the Missing on either side of the stairs. The Courts contain names of those missing or buried at sea from American wars in the Pacific – World War II, Korea and Vietnam. The World War II missing from the southwest Pacific are memorialized at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, where the names are alphabetized within each military branch.

Punchbowl (Honolulu Memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific)

The architects of the Honolulu Memorial, Weihe, Frick & Kruse, may have been influenced by Edwin Lutyens’ World War I Memorial to the Missing of the Somme in Thiepval, France. That memorial is an open air building with a wide staircase leading to a memorial stone. On either side of the stairs are areas which could be termed “courts of the missing,” formed by interwoven structural arches. (I have written extensively about the Somme memorial in IsisInBlog.)

The names in France are in a full hierarchy, beginning with British Army Order of Precedence and continuing in a listing by rank. World War I British recruitment strategy built military units from individual towns. So this arrangement keeps neighbors together, but it does not express equality. At the Honolulu Memorial, names are organized first by war, then by military branch, then alphabetized.

Those who died on the USS Arizona, and whose bodies were not recovered, are declared buried at sea and therefore missing, so Rear Admiral Kidd is on the Honolulu Memorial. As the highest ranking officer to die at Pearl Harbor, his name is among the K’s with other Navy personnel missing from World War II. Here he is surrounded not only by his men on the Arizona, but also by almost 12,000 Navy personnel whose bodies, like his, were not found.

Photo Credits

Heiter. (n.d.). Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, USN (1884-1941) Naval Historical Center. Photo NH 48579-KN. http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pers-us/uspers-k/ic-kidd.htm

Victor-nv. (April 13, 2010). Anchor of the USS Arizona on display at Wesley Bolin Memorial Plaza, Phoenix, AZ. Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arizona_anchor_bolin_plaza.JPG

Katherine Bertolucci. (November 29, 2011). Rear Admiral Kidd among His Men at the USS Arizona Anchor Memorial in Phoenix.

Jayme Pastoric. (May 23, 2002). USS Arizona Memorial. U.S. Navy photo 020523-N-9769P-057. http://www.navy.mil/view_single.asp?id=1643

Wally Gobetz. (May 26, 2010). USS Oklahoma Memorial. http://www.flickr.com/photos/wallyg/4791732465/

Rosa Say. (August 20, 2008). The USS Utah Memorial. http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosasay/2792163602/

Wally Gobetz. (May 26, 2010). USS Arizona Memorial Visitors Center – Remembrance Circle. http://www.flickr.com/photos/wallyg/4781085494/in/photostream

Jiang. (December 22, 2005). Punchbowl. Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Punchbowl_%281236%29.JPG

Follow

Follow

The

The