Heroes of a Revolution: Memorials Discovered by the Simmons’ May, 2011 Strategic Information Arrangement Class

(During the CE Course on Strategic Information Arrangement that I teach at Simmons College, participants have the opportunity to write about a memorial in their local area for possible inclusion in my Memorial or Veterans Day blog post. Today we have a Revolutionary War theme, perhaps appropriate for a college located in Boston.)

The night of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere saw two lights in the Old North Church and began his famous ride, alerting colonists in the Boston area that British troops were crossing the Charles River. Near midnight, he reached the town of Medford, where Dr. Martin Herrick joined the ride, heading toward Stoneham. Revere continued on to Lexington. The militia assembled at dawn on the Green and the first shots were fired. The British then retreated back toward Boston, reaching Menotomy (now Arlington) around 4pm. It was there the war really began. This brutal battle caused the most casualties of April 19 on both sides, including civilians. Two men from Medford, William Polly and Henry Putnam, were mortally injured.

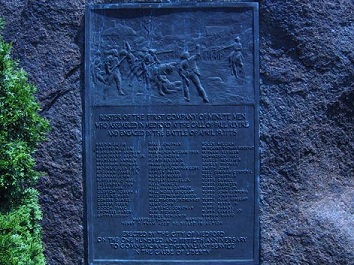

Christina Anderson of ABT Associates, found a memorial to the Minute Men of Medford, located near the public library. It was erected for the 150th anniversary of the American Revolution. The 60 names are in alphabetical order, with the exception of Henry Putnam, who appears at the bottom described as “Aged 62 Killed in Action.” Why was Henry Putnam given this honor and not William Polly?

The Medford Historical Society has limited hours, but volunteers Jerry Hershkowitz and Mike Bradford were there when I needed them. So I called and asked about William Polly. The key to the mystery is the inscription at the top of the memorial which reads “Roster of the First Company of Minute Men Who Assembled in Medford at the Call of Paul Revere and Engaged in the Battle of April 19, 1775.” According to Hershkowitz, Putnam was exempted from the militia because he was too old, but he went to the battle anyway and got killed. On the memorial, there is no way of knowing that William Polly also died. I learned about it accidentally in my research.

If we think about this in terms of information arrangement, we have three facets: those on the roster (59), those not on the roster (1), and an intersection of those who died (2). Perhaps Putnam received extra information to explain his inclusion with the roster, but it creates confusion because someone else died and there is no acknowledgement.

Dating from 1925, the Medford plaque is fairly early among memorials in listing names. That began in earnest with the First World War. In 1936, Medford’s Lawrence Light Guard erected a plaque in the lobby of their armory with the names of Guards who served in WWI. Hershkowitz took a short walk to the armory, now in commercial use. He noted some names have stars, which he believes indicates those who died, a simple solution fully honoring their sacrifice.

If Menotomy was the beginning of the Revolutionary War, Saratoga was the turning point in September and October, 1777. A major victory for the Americans, its hero was Benedict Arnold. Serving under Horatio Gates, he commanded the troops on September 19. The British won this first day, but suffered major casualties. After the battle, Arnold quarreled with Gates and was relieved of his command. Then in the second battle on October 7, Arnold disobeyed orders and entered the battlefield, taking command and leading the troops to a decisive victory. This win caused the French to enter the war in support of the Americans, an important factor contributing to the success of the Revolution.

Arnold was injured in the battle and unable to return to combat, which may have influenced his treason in 1780. He also felt a lack of acknowledgment for his military achievements and thought the Continental Congress was trying to cheat him financially. Then he married a Loyalist woman prior to the treason. Towards the end of the war, he fought again, this time for the British.

Julie Vittengl of GlobalSpec found the Boot Monument at Saratoga National Historical Park in New York. Erected by Civil War General and historian John Watts de Peyster, it honors Benedict Arnold as “the most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army,” yet only shows his injured leg and does not name him. Saratoga’s victory obelisk has four places for the four generals involved. Arnold’s space is empty. Likewise at West Point, the site of his treason, Arnold’s place as a Revolutionary War General is empty showing only his rank and his birthday.

In the book, Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy, 2003, geographer Kenneth E. Foote identifies four responses to high profile painful events: sanctification, designation, rectification, and obliteration. Sanctification creates a sacred space, such as the Saratoga National Historical Park. Designation tends to be an onsite plaque or small memorial acknowledging the event. While the Medford war memorials are not sited where the actual events happened, they would be examples of designation. Rectification returns the site to productive use. The World Trade Center is undergoing rectification, with office space in new buildings available for lease. At the same time, the sites’s National September 11 Memorial and Museum is sanctification. Obliteration removes the location from our memory. Buildings at crime scenes are sometimes torn down and the vacant lot neglected.

Our national feeling about Benedict Arnold wavers between designation and obliteration. He served his country in many battles, not just Saratoga. He commanded that decisive battle, setting the stage for our eventual victory. Then he turned against us. We cannot remove him from history, but we can remove his name from our places of honor. After all, thanks to men like William Polly and Henry Putnam, we won the war and we built our new nation.

(A note on resources not mentioned in the article. I discovered William Polly in The Minute Men: The First Fight by John Galvin, 1996, and in Paul Rever’s Ride by David Hackett Fischer, 1994. An article by Thomas Fleming, 2010, “Battle of Menotomy: First Blood, 1775,” clearly described that event. Jerry Hershkowitz’ primary resource, other than the town itself, was Medford in the Revolution, by Helen Tilden Wild, 1903. I relied on Wikipedia for information about Benedict Arnold, specifically the pages for Arnold, the Battles of Saratoga, the Boot Monument, and Saratoga National Historical Park. Saratoga and Lexington & Concord are both described in the Encyclopedia of Battles in North America: 1517-1916 by L. Edward & Sarah J. Purcell, 2000. Photo Credits: Medford Minute Man Memorial by Christina Anderson, 2011; Arnold-Boot by Americasroof at Wikimedia Commons, 2006.)

Follow

Follow