Memorials for Veterans Day, Discovered by the Simmons Strategic Information Arrangement Class, November 2010

A lively Strategic Information Arrangement class continues this month in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science CE program at Simmons College. The four week class looks at arrangement strategies and persuasive uses of arrangement, including a one week section about names on memorials. For the May 2010 class, I wrote a Memorial Day blog describing memorials found by class members. In a new tradition, today’s post honors Veterans Day with memorials found by the current class.

HARVARD MEMORIAL HALL TRANSEPT

Harvard University provides an elegant memorial to its “associates” who died fighting for the Union in the Civil War. We learned of this memorial from Jennifer Beauregard, the university’s Assistant Director for Alumni Affairs and Development Library Services. Located in the Transept of Memorial Hall, the 136 names on 28 wall plaques are listed by school and by class, in alphabetical order within each class. There is one plaque out of order, but we do not know the reason for that.

The memorial’s donor specified the exclusion of names of Harvard Confederates. In 2006, artist Brian Tolle built his “Deep Wounds” installation on the floor of the Transept, calling attention to these Harvard soldiers who also died. As people walked across his lit floor, their footsteps created a “blister” of light behind them, revealing information about a Harvard Confederate, everything but his name. They were organized so Union and Confederate soldiers from the same class were near each other.

This got me wondering if there are Civil War memorials honoring both sides. Certainly other colleges and towns, especially in border states, would have Union and Confederate losses. I didn’t find anything in brief research. However, I did find a Wikipedia article about the Gettysburg “Great Reunion of 1913,”, which included all participants.

LONGMEADOW, MASSACHUSETS TOWN GREEN

Elizabeth Ryan, Director of Social Media at the start-up company, Textifer, found a war memorial on her Town Green in Longmeadow, MA. She says names are arranged by war and then in alphabetical order. Most of the names are from World War II. Photos on the town website, and a personal communication from a town employee, indicate a separate memorial for World War I.

Many towns in the United States and Britain have war memorials. There is even a British memorial honoring those who died from a single city block. I remember visiting the World War II memorial in San Francisco to look at the names of my mother’s friends. Before moving to Phoenix, I lived in Healdsburg in California’s wine country. Just like Longmeadow, they have a small memorial in the town square for those lost in wars.

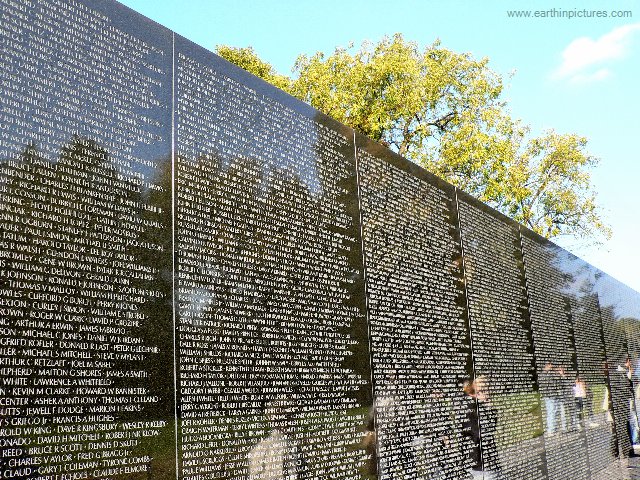

SHUTTLE CHALLENGER MEMORIAL

Jeanne Goss of the Research Department at the industrial supply company Grainger told us about the Shuttle Challenger Memorial (pictured) at Arlington National Cemetery. This is a small memorial, a headstone really, marking the unidentified remains of the Challenger’s crew. Identified remains were returned to their families. This has a persuasive element in that the names are arranged in a circle, a geometric shape emphasizing equality. Yet the names are actually in a complex ordering.

According to a personal (and very fast) communication from NASA, there is only one crew leader, the Commander, and everyone else is equal. However, it is my observation that the Challenger crew names are frequently listed in the same order: Commander, Pilot, Mission Specialists in alphabetical order, and civilians in alphabetical order. This is how they are listed in the Challenger Center for Space Science Education, founded by families of the crew, and how they are listed in official NASA biographies.

However, that is not how they are arranged in the official photograph. The Commander is in the center first row, with the Pilot at his right hand. The first Mission Specialist sits at his left, with the remaining four in the second row but not in the above order.

The arrangement in the photograph is partially repeated on the memorial. Commander Dick Scobee is at the top with Challenger pointing at him like an arrow. At his right (our left) is the Pilot, Michael Smith. As in the photo, Mission Specialist Ron McNair is at Scobee’s left. Then below Smith, the remaining four crew members are listed counterclockwise as described above: Mission Specialist Ellison Onizuka, Mission Specialist Judy Resnik, civilian engineer Gregory Jarvis, and civilian teacher Christa McAuliffe. The artist used several elements to select placement for each name, yet the circle creates a primary impression of equality, which is how NASA organizes its crews.

Correction: I originally wrote this on Veterans Day weekend, which impeded researching primary sources. However, on Veterans Day, after I posted, I received a response from Cheri Winkler of the Challenger Center for Space Science Education. She had asked Dick Scobee’s widow, June Scobee Rodgers, about the name arrangement. Here is Dr. Scobee’s response:

“Fascinating question. Commander Scobee, then pilot Mike Smith is right. The three mission specialists are alphabetized, then the payload specialist Jarvis, the private citizen Christa. If it were based on position of job on crew, Judy Resnik would come first of the 3 mission specialists.”

VENDOME FIREFIGHTERS MEMORIAL

A strategy emphasizing different characteristics is taken by Boston’s Vendome Firefighters Memorial, found by Andrea Goodman, Senior Information Specialist at the economics consulting firm Cornerstone Research. This semi-circular wall honors nine Boston firefighters who lost their lives fighting a 1972 fire in the Vendome Hotel. It is the largest number of Boston firefighters to have died in a single incident. The hotel can be seen above the memorial’s arc. At that point rests a realistic sculpture of a helmet and jacket, “lying as if left there by a firefighter on the day of the fire.”

On the memorial, the nine names are listed in alphabetical order, expressing equality. However, on the memorial’s website, the names seem to be listed in hierarchy of rank, with the two lieutenants first. Then in the PDF program for the dedication, they are in a chronology of service, by date of entry into the Boston Fire Department. There is honor in length of service, and there is honor in having a higher rank, just as it often appropriate to show equality. The developers of this memorial gave us all three.

GUILFORD NATIONAL MILITARY PARK

Lists of names are a relatively new development in memorials due to our increasing respect for enlisted personnel and our better record keeping. For many centuries, memorials were statues of great military leaders. That is the strategy of the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in Greensboro, NC, discovered by Mary Lane, a Library Manger in that city. The site of a Revolutionary War battle, its centerpiece is a massive statue of General Nathaniel Greene on his horse. Persuasive use of size and location convey the impression that this is an important man and an important place.

There are many other memorial structures in the park. The idea was to locate these on the sites of actual battle events. Organizing information by location, whether on the land itself or on a website, is a geographic arrangement, but there’s a hitch here. Like the Alamo, where they destroyed an historic building to make the area more beautiful, the Guilford Courthouse is a park not an accurate historic site. For one thing, early promoters were not able to acquire all the land, so they redesigned the battle to fit the land they did have. Current park policy is to relocate these errant memorials to their accurate locations, but some are too big for that.

IRISH HUNGER MEMORIAL

The Irish Hunger Memorial in New York City, discovered by Meghan Sullivan, a Knowledge Management Information Architect with the Kaplan education company, honors the millions who died in the Great Irish Famine of the 1840’s or who emigrated from Ireland, many to the United States. A low cantilevered roof on a half acre, it is landscaped to look like the Irish countryside, complete with an actual hut from that era. You enter or depart the hut though a hallway with streaming illuminated quotations about hunger, both during the Famine and in our modern times. Meghan’s observations, along with a New Yorker review, indicate these quotes appear at random.

The rooftop garden contains large stones engraved with names of Irish counties. There seems to be an arrangement here, but we have not determined what it is. A PDF brochure lists counties in alphabetical order and shows their locations with a numbering system. However the numbers do not relate to the alphabet nor are they contiguous on the map. They also don’t relate to the counties’ locations in Ireland. I found a map showing population changes during the Famine, and that doesn’t seem to be it.

Perhaps the arrangement is explained somewhere at the memorial, but the map would be a good place for this description. While there is a grand tradition of written reviews, we usually don’t explain art at the site of the art itself. We expect the viewer to create their own impression from the cues given by the artist. One’s interpretation of the piece may be quite different from what the artist intended and that’s acceptable and encouraged.

But arrangement is different from other artistic elements. If not articulated, a structured arrangement exists only in the artist’s mind. As part of artistic display, organizational choices contribute to our understanding. But if there are no cues, we have a guessing game, especially when choices are complex. (See my article about the Wittenbergplatz Holocaust Memorial for another example of an unexplained arrangement.)

At the Irish Hunger Memorial, someone made a decision about placing stones and about assigning numbers unrelated to that placement. The reasons are not explained. Our understanding of the memorial, and our thoughts about hunger, would be enhanced if this artistic element was made visible.

For this article, I also made arrangement decisions. Following the example of the Shuttle Challenger Memorial, I created two categories – memorials with and without names. Since the unit is primarily about how names are arranged on memorials, I placed that category first. Within each category, the memorials are in alphabetical order.

It took me a paragraph to explain my strategy, one reason perhaps why artistic arrangements are not often explained. But that could easily be shortened, especially if we assume certain organizing structures, such as the alphabet, are obvious.

Arrangement: Memorials with names, Memorials without names

Thank you to those who served our country in war, in fighting fires, and in exploring new territory. Thank you to the immigrants who gave so many of us a place in this great country. Thank you to those serving us today who, with great sadness, will one day be memorialized.

Photo Credit: Shuttle Challenger Memorial by M. R. Patterson

Follow

Follow