Arranging to Persuade: Self-Monitoring or Taking the Tedium Out of Tracking

B. J. Fogg’s Principle of Self-Monitoring: Applying computing technology to eliminate the tedium of tracking performance or status helps people to achieve pre-determined goals or outcomes.

Self-monitoring, the fifth persuasive technique from B J Fogg’s book, Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do, includes such devices as a smart jump rope and a heart rate monitor. As you exercise, the jump rope’s handles display the number of calories you’re burning. The heart monitor shows the rate your heart is pumping. Fogg explains that “this type of tool allows people to monitor themselves to modify their attitudes or behaviors to achieve a predetermined goal or outcome.” The exercise machines at my gym have similar devices. I sometimes pedal faster to reach a mileage goal before the end of the spinning class.

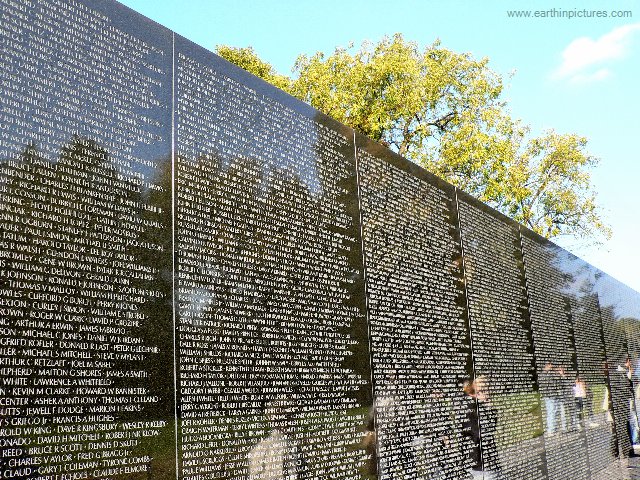

We’ve been examining how information arrangement uses Fogg’s persuasive principles at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Self-monitoring is the one principle not in use at the VVM. However, we can look at the facet-based search technique to see how self-monitoring works with this type of information arrangement.

Facets are a method for presenting the defined attributes of online records in a finite collection. Users select and deselect attributes as the search proceeds, enabling them to monitor and modify the results. This is especially valuable for online sales.

Let’s say you want to buy a shirt. A clothing website displays all its available shirts with a list of facets: color, fabric, style, etc. You select blue, so now you only see blue shirts in available fabrics and styles. If any fabrics or styles do not have blue, you no longer see them. You select cotton. Other fabrics are eliminated and you only see blue cotton shirts in the available styles. Now you realize you want a polo shirt, but that’s not available in blue cotton. So you modify your search by deselecting blue, retaining cotton, and choosing the polo style. You see cotton polo shirts in the available colors, including a very nice red that you buy.

One example of this technology is the open source Project Blacklight. Boston’s WGBH uses Blacklight for its Open Vault Media Library and Archives. At the Open Vault search page, select a category under browse. Now on the left under the heading “Narrow,” you’ll see a list of available facets for that category. As you continue selecting, your choices appear at the top of the list. You can add or remove attributes to modify the search.

Facets provide a satisfying search experience because there is no guessing. It’s a process that searches a finite collection, only showing available items, so you always have an accurately populated screen. As you select and deselect, you see different aspects of the collection. If the online store doesn’t have blue polo shirts, a simple modification shows you they do have one in this nice shade of red.

Illustration used with permission from Microsoft.

Follow

Follow