Honoring American Slaves

For Memorial Day 2016, we look at two memorials to American slaves, the African Burying Ground in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the Wessyngton Plantation near Springfield, Tennessee. Memorial Day began as Decoration Day to honor the military dead of the Civil War. It’s controversial whether the day began as a Union or Confederate ceremony, but the first official event happened at the Union’s Arlington Cemetery on May 5, 1868.

Tonight the History Channel begins airing a remake of Alex Haley’s Roots, the story of his ancestors’ experiences in slavery, the institution the states were all fighting about. Some say they fought over state’s rights, but Confederate papers of secession make it clear the right they were interested in was slavery. One example is the Texas “Declaration of Causes,” essentially 1600 words about slavery, although they added 50 words about the Federal government not paying enough money to secure the Mexican border.

The first ancestors of today’s African-Americans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619. That’s one year before the Mayflower landed. About three decades later in 1652, Rhode Island passed the first abolition law. It wasn’t enforced nor was a similar attempt in 1675. Newport, RI eventually became a major point of entry for kidnapped Africans to be sold into slavery. Seaports were vulnerable to the lure of riches provided by the sale of abducted humans. The next attempt at abolition was well inland at a 1688 Quaker meeting in Germantown, Pennsylvania.

Portsmouth, NH was another profitable slave seaport. That state began its gradual rise toward ending slavery in 1788, a task not fully completed in the state until 1857. Portsmouth’s slave importing industry died in 1808 with the Federal Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves. After passage, smuggling kidnapped Africans into the southern states continued until the Civil War, when we finally rid ourselves of slavery at the cost of about 400,000 Union soldiers’ lives. Almost as many Confederate soldiers died fighting for the right to imprison other human beings for their free labor.

Throughout these events of slavery, abolition and war, African-Americans lived and died in Portsmouth. When they died, some were buried in unmarked graves in a burial ground at the edge of town. As Portsmouth grew, that edge became the center. Structures that are still standing were built over the burial site. It was paved with a street and a sewer line under the street. The town conveniently forgot about the old burial ground, despite bones showing up every so often. Workers even ran a pipe through caskets at some time in the past.

In 2003, the sewer needed an upgrade. This time Portsmouth was ready with an archaeologist on hand in case anything interesting turned up. And something very interesting did – thirteen coffins. Now after centuries of debasing the long lost cemetery, Portsmouth finally honored its own history. They only found thirteen bodies, but the estimate is that as many as 200 people may be buried there. The city closed that block to traffic and built a memorial, the African Burying Ground, designed by artist Jerome Meadows.

On May 26, 2015 the thirteen bodies were moved to a central area in the block-long memorial in a magnificent reburial ceremony with new handmade coffins and a horse drawn hearse. Because these people died in the 18th Century, they may have been native Africans, so each coffin contained a small item from Africa. An earlier consecration ceremony included African rituals perhaps familiar to some of the people buried in the memorial and in the larger burying ground.

The African Burying Ground does not include a list of names. There is no way of knowing who is buried there because nobody bothered to give them headstones. However at the consecration ceremony, individuals read a list of names of all slaves who lived in Portsmouth or traveled through the slavery seaport. The list was compiled by Valerie Cunningham, co-author with Mark J. Sammons of Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage. This is a remarkable list, given the difficulty of working with materials about slaves, however I was not able to easily find this list of enslaved individuals. Including a PDF of these names on the memorial’s website would give honor to them.

In a video of the ceremony, you can see people reading some of the names in alphabetical order by first name. There is a slight variation for children who have no name and are simply listed, for example, as “Child of Becky Quint” where, presumably, the mother is also a slave and listed under B for Becky. In my previous article, “Patcham Down Indian Forces Cremation Memorial,” I discussed the use of first names as a method for trivializing a group of people. That is not what is happening in this ceremony.

American slaves were frequently not given last names, so practicality may be the reason for alphabetizing by first name. However in the video’s small sample, we only have one example of an adult without a last name, “Child of Neptune.” If a slave had a last name, it was often the last name of the previous owner, so organizing by last name would honor owners rather than the people of African heritage whose memorial was being consecrated. By reading the names in alphabetical order by first name, it is the Africans who are honored, not their owners.

We do need to acknowledge that white owners often didn’t bother with last names for slaves as a method of dehumanization. The survival of slavery as an institution depended on dehumanizing the victims. Those who benefited from slavery had to convince otherwise honorable whites that Africans were not fully human and therefore deserved to be held in slavery.

Examples of this come from Thomas Jefferson’s book, Notes on the State of Virginia. The section on slaves declares “the preference of the Oranootan for the black women over those of his own species” (p. 145). Jefferson apparently believed that African women copulated with apes. He did acknowledge that African-American men could be very brave, explaining it by writing “this may proceed from a want of forethought, which prevents their seeing a danger till it be present” (p. 146). Jefferson is saying that, like animals, Africans don’t think ahead. Despite his interest in science, Jefferson came to a racist conclusion first and then fit the evidence to his conclusion, although I doubt he had any evidence at all for his statement about Oranootans.

I found no evidence that Jefferson treated his slaves like animals, but other southern slave holders did. Mia Bay, in her book The White Image in the Black Mind: African-American Ideas About White People, 1830-1925, quotes Lizzie Williams, a Mississippi slave, “There was a trough out in the yard . . . (T)hey poured the mush and milk in and us children and the dogs would all crowd around it and eat together. . . . (W)e sure had to be in a hurry about it because the dogs would get it all if we didn’t” (p. 133). In the book, the quote is in dialect, which I revised to the correct English spelling. During my research, I noticed that almost all quotations from slaves and former slaves are in dialect, another method for demeaning them. We don’t, for example, continuously quote in dialect people with broad New England accents. Soujourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech was transcribed into a deep southern slave dialect even though she was from New York and spoke English with a slight Dutch cadence.

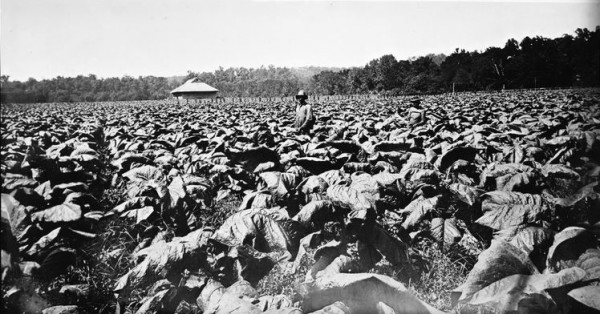

About 20 years after the Revolution, Joseph Washington founded the Wessyngton Plantation near what is now Springfield, Tennessee. It operated until the Civil War as the largest tobacco plantation in the United States and the second largest in the world. The Washingtons’ strategy was to keep slave families together. They only sold two people, one woman at the beginning of their operation because they needed cash and the other because he continually ran away. However, these slave families still did not have last names. Sometimes a group of slaves might be added through a marriage of the white owning family. In that case, the added slaves would be given the last name of the previous owner to identify them as a group.

In the 1970s, pre-teen John F. Baker Jr. became interested in his family history. A descendent of the Washington slaves, his large extended family still lived in the area of the Wessyngton Plantation. Because he started young, he was able to interview people who had known relatives who had been slaves. He was also aided by meticulous records kept by the owning family and donated to an archive. Baker’s research studied both the black and white Washington families and resulted in his book The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom.

Given the emphasis on families and the lack of slave sales, one might think that Wessyngton was the mythical plantation of contented slaves and benevolent owners. The lie in that mythology is evident in Baker’s quote from a woman who was told by a former female slave, “If a white man told you to lay, you had to lay, like it or not” (pp. 104-105). He also writes about slaves punished for praying for freedom and a child whipped for being sick. According to Baker, the Wessyngton slaves had a clear sense of morality. It was wrong to steal from other slaves, but there was no sin in stealing from the white owners, since their theft of freedom, and the abuses arising from that theft, branded the whites as criminals.

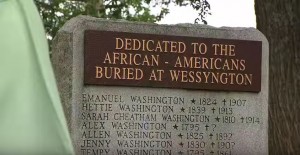

Baker built two memorials on the Wessyngton Plantation property, both financed by descendants of the white family. The first lists names of slaves interred in a cemetery on the Wessyngton property, with names in no discernible order, although two of Baker’s great-great grandparents, Emanuel and Hettie Washington, are in the first two places. The memorial includes birth and death dates, if known.

The second and larger memorial lists the names of all Wessyngton slaves in alphabetical order by first name, with birth and death dates included, if known, along with a designation for men who served with the Union Army’s United States Colored Troops in the Civil War. Perhaps some of them fought in the USCT action at the infamous Battle of the Crater during the Siege of Petersburg, which was an early use of trench warfare. This battlefield is currently in the news because of its recent looting in an archaeological theft. On today’s Memorial Day, we honor the Wessyngton men who served with the USCT.

Bill Henry Scott (died 1929), Carey Washington (d. after 1863), Dick Lewis (d. after 1863), Granville Stroud Washington (d. after 1863), Henry Lewis (d. 1889), Hezekiah Tom Washington (d. 1918), Jacob Washington (d. 1903), Joseph Scott (d. 1932), Miles Washington (d. 1903), Otho Lewis Washington, Sr. (d. 1920), Reuben Cheatham Washington (d. 1894), William Washington (d. 1865)

Like the Portsmouth oral list of names, alphabetizing by first name at Wessyngton honors individual slaves rather than the white ownership families. There is also a practical aspect since the vast majority of them have the last name of Washington. Baker wrote that no slaves were given the name of Washington prior to Emancipation, so in the two memorials, he must have assigned that last name to those who died before that date. This is a logical thing for him to do because their descendants took the name upon Emancipation.

When they were freed, slaves had the opportunity to select their own last name. They often took the last name of their former owners, a familiar tradition. Many Wessyngton slaves took the name of Washington, which was popular with other freed slaves as the name of a President. Jefferson was also a popular choice for the same reason. The newly freed slaves probably did not realize that when Thomas Jefferson wrote “all men are created equal,” he did not believe that Africans belonged to the category of men. As a misogynist, Jefferson may have intentionally excluded women, but that’s another story, except to note that in his book, African males are unintentionally brave and the females consort with apes.

Both these memorials, the African Burying Ground and the Wessyngton Plantation, take a tradition intended to dehumanize a group of people and use it to fully honor them. Slaves were frequently not given last names as one of many ways to show inferiority. If they were given a last name, it was the name of an owner, thus validating the slaver’s claim to own another human being.

Organizing the names of slaves by first name invalidates that claim. It shows that you can’t own another human being. You can imprison them, assault them, force them to work, and treat them like animals, but you can never really own someone with a human brain. Dr. Bay shows this in an anecdote from her book, The White Image in the Black Mind. A female slave on the auction block in Texas demonstrated her opinion of the event by yelling, “Weigh them cattle. Weigh them cattle” (p. 133).

I think the white ownership class understood that you cannot own a human being. That’s why people like Thomas Jefferson lied to themselves about the humanity of their slaves. They lied for the two centuries of slavery; they lied after the Civil War and through to the Civil Rights Movement and beyond. We continue to suffer from their lies, but these two memorials, the African Burying Ground and the Wessyngton Plantation, help us to understand the truth of our history and how that shapes our current culture.

Sources of Graphics

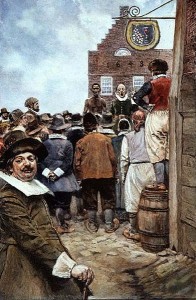

First slave auction in New Amsterdam, 1655. Wikimedia Commons

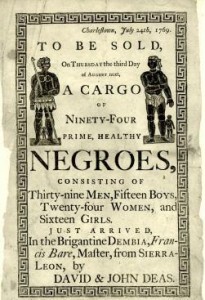

Ad for slave auction from a newly arrived ship. Slave Auction Ad, Wikimedia Commons

Finding the first coffin. Portsmouth Remembers – African Burying Ground, YouTube screenshot

Model of sculpture by Jerome Meadows at the African Burying Ground. “In Honor of Those Forgotten,” Project Introduction Booklet PDF

Tobacco farming at Wessyngton Plantation. View of Tobacco Farming with Unnamed Structure, Wikimedia Commons

First Wessyngton Memorial. Wessyngton Plantation – A Family’s Road to Freedom, YouTube screenshot

Second Wessyngton Memorial. Memorial Monument Dedication Ceremony, African American Cemetery, YouTube screenshot

Follow

Follow