(This post acknowledges October 12 as a day honoring Christopher Columbus, who promoted European colonization of the New World, thus beginning the desecration of North and South America’s original civilizations.)

Michael Arad, designer of the World Trade Center 9/11 memorial, originally envisioned a random name arrangement. He felt the imposition of any organized arrangement strategy would cause “grief and anguish.” However, it soon became clear that it was the randomization of the names that was causing the grief and anguish.

Families of those who died understood that random trivializes life and death. They wanted the name arrangement to indicate affiliation, such as business, friends and family, along with details including the names of the businesses, ages of the victims, and floor numbers. Family groups fought for this vision by refusing to donate to the memorial, demonstrating the emotional power of information arrangement. The designers compromised with a name arrangement that is intended to look random but is actually a highly organized list of names with “meaningful adjacencies.” This is not a simple structure with one set of arrangement rules. Each name is placed according to individualized criteria.

Both the Vietnam Veterans Memorial (VVM) and the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme incorporate meaningful adjacencies, as does every arrangement method, except random. A lack of meaningful adjacencies defines random. The VVM lists names in chronological order. Those who died on a given date are adjacent on the memorial. Military survivors can find friends by finding their own time of service at a designated place on The Wall.

In France, the Somme memorial from World War I achieves the same goal with a different strategy. Most of the 72,000 names listed on that memorial went missing on the same day, so chronology has no meaning. These names are listed by military units, bringing people together because of recruitment by towns. British military units in World War I often consisted of men from a single area, a method that has since been abandoned. Whole units died during the surge on July 1, 1916. Today, people from these towns can find their missing generation of young men in one place on the massive walls.

These two arrangements are brilliant in their simplicity, but they organize groups whose members have similar defining characteristics. That is not the case with the World Trade Center memorial. People who died on September 11, 2001 were working or they were visiting a building, flying in an airplane or trying to rescue others. They were with their co-workers, perhaps with their families, or they were alone. They did not have a common reason for being where they died.

When the arrangement controversy was raging, I submitted a proposal for a geographic structure and that is essentially what is being used. It should be noted that I have no evidence that anyone read my proposal. Arrangement by location was always an obvious option for this memorial. My suggestion was based solidly on location to the point of listing people on airplanes by their seat assignments. People who know each other sit next to each other, so meaningful adjacency is achieved.I also wanted the names from the towers listed by floor. Again, people on the same floor know each other. This method added meaning by demonstrating that most people below a certain floor escaped and most above a certain floor did not. To my mind, a full geographic arrangement illustrates the tragedy more completely by showing where people were and who they were with when they died.

The selected memorial design and its name arrangement include panels in two squares that surround two pools, one for each tower and the airplane that crashed into it. The Pentagon and its airplane, the First Responders, and Flight 93 are with the South Tower. Those who died in the 1993 attack are with the North Tower.

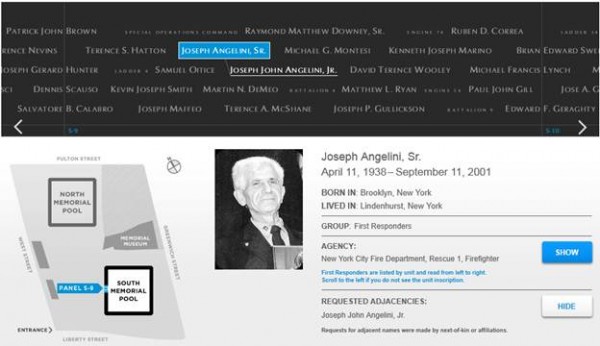

In all, there are nine groups. The title of each group is inscribed at the beginning of its associated names. For example, “World Trade Center” appears before the names of those who died in the North or South Tower. The names are then arranged by affiliation, which is not indicated, except for the First Responder agencies and units, who are reprieved of the need to look random.

In general the families were not happy with this compromise. They wanted more information next to each name, specifically age, company and floor. My proposal would resolve company and floor, and also included ages with each name. I want to say that the struggle here shows the folly of allowing non-organizersto develop such an important name arrangement. People who don’t understand the impact of organized information thought up random. But there are other factors to consider here. Does every business want the kind of advertising that comes with being part of a tragedy?

Once random was abandoned, the designers encouraged individual participation. Next-of-kin could request placement near another name, a friend in the same company perhaps, or a loved one who worked for a different business. Companies could request that names be arranged by department or work unit. This resulting structure is therefore a puzzle for the designers to solve. We can assume there were trade-offs.

The names of a married couple who worked for different companies are listed together. The couple has three affiliations – to each other and to their separate companies. This could be resolved by taking the married couple out of their respective companies and placing them separately or by putting their two companies next to each other. But this couple may not be the only ones in their companies with cross-corporate affiliations.

The designers were careful to hedge their promises with phrases like “to the best of our abilities.” They understood subjective decisions would have to be made. For example, if there has to be a choice, is it more important to put a married couple together than two best friends?

My fully location based arrangement eliminated subjectivity. However, the married couple would not be together forever on the memorial. Their names would be sitting in their separate offices. The chosen arrangement is a compromise with many mistakes, pretending to be random being especially egregious. But individual attention to the placement of each name is a new idea in memorial name arrangement. It came about accidentally when the families refused to let the designers abandon their responsibility to those who died. The families didn’t get everything they wanted, but what they did get was personalized attention for each name engraved at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

(This post is part of a series about how names are arranged on memorial structures. I returned to the series when I prepared an online course on Strategic Information Arrangement for Simmons College. Other posts in the series can be found in the IsisInBlog Directory under “Names on a Memorial Series.)

The National September 11 Memorial opened today on the tenth anniversary of the attacks, expressing our grief and our memories of that horrible day. As in all memorials with names, the arrangement forms our perception of those who died.

The National September 11 Memorial opened today on the tenth anniversary of the attacks, expressing our grief and our memories of that horrible day. As in all memorials with names, the arrangement forms our perception of those who died.

Follow

Follow