Patcham Down Indian Forces Cremation Memorial

Built in 1787, the Royal Pavilion in Brighton was as an extravagant beach house for the Prince of Wales who became King George IV. Over the years, it evolved into the appearance of an Indian palace. Queen Victoria preferred another summer retreat and sold the Pavilion in 1850 to the City of Brighton. In World War I, it was converted into a hospital for the British Indian Forces. After they left, the facility rehabilitated veterans with amputated limbs. The Pavilion eventually returned to the City and now is a prominent tourist attraction.

Britons who die in war are always honored by name, preferably on their gravestones. For those who are missing, and this was a huge problem in World War I, names are listed on monuments, such as the massive Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. But 53 Hindus and Sikhs in the British Indian Forces fell through the cracks. They died in the Royal Pavilion war hospital and were cremated in keeping with their religions. With no burial, their names were not on gravestones, yet they weren’t missing, so they couldn’t be listed on a Memorial to the Missing.

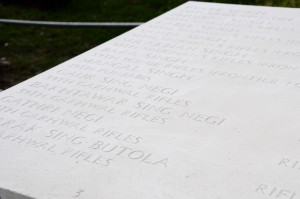

In 1920, the City of Brighton and the India Office built a memorial temple, the Chattri Memorial, on the site of the cremations. It was not until 2010 that the 53 names were listed on the Patcham Down Indian Forces Cremation Memorial, built by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission on the same property. As in all British memorials, the names are listed with their military units in Order of Precedence, a chronological order based on each unit’s date of establishment. It’s difficult to visually perceive the further information structure because only a few names are listed within single units. These are soldiers who survived different battles, made it across the Channel to a hospital on the coast and died of their wounds in that hospital. Nineteen Muslim soldiers from the British Indian Forces also died at the Royal Pavilion, but they were buried so their names are on gravestones.

On the larger memorials, the military unit is carved once with names below. Here, each man has the full name of his unit below his own name. They are listed in their units by rank, which is not indicated, and within rank by alphabetical order. On this memorial and on the Somme memorial, alphabetical order for South Asians is by first name. On the Somme memorial, European members of the British Indian Forces are listed last name first.

Why the discrepancy? Is it practicality or racism or both? Many South Asian names are quite common. One third of the men on the Patcham Down Memorial have the last name of Singh. Another name, Gurung, is owned by 15% of Nepalis. Only one first name is repeated, giving 52 unique first names. So from an information management standpoint, the first name provides more value in identifying individuals.

In the tradition of the British colonizers, people who are socially higher are addressed by last names, while people who are lower are addressed by first names. The organizing structure of first name first may have been based on practicality, but its use would have reminded Europeans that, in their eyes, South Asians were less valuable. This would be the case even if South Asians didn’t acknowledge the use of first names as a diminishment.

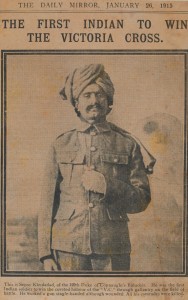

Let’s take a look at the first South Asian recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest British military honor. Non-European members of the British Indian Forces were not allowed to receive the VC before 1911. Khudadad Khan, a Muslim, was in the 129th Duke of Connaught’s Own Baluchi’s with the rank of Sepoy or Private. His last name is now the 80th most common name in Britain. When Khan’s unit arrived in October 1914 at the pivotal First Battle of Ypres, the fight was already raging. His machine-gun team was sent to stop the Germans from getting to a port. Eventually every other soldier in his gunnery group died. Injured, Khan kept shooting and held the Germans long enough for reinforcements to arrive. Because of his extreme effort, the British saved the port. With him, the military finally awarded the Victoria Cross to a non-European member of the British Indian Forces. Kahn died at the age of 82 in 1971. He is honored with a statue in front of the Pakistani Army Museum in Rawalpindi.

What if Khan had not kept shooting and the Germans had taken that port? Would they have won the First Battle of Ypres? How would that have changed the war? Without Khudadad Khan, who wins World War I? Yet in a newspaper article about his award, Kahn is called Sepoy Khudadad. The Daily Mirror doesn’t even bother to give his last name, signaling to all Londoners the relative social status of this astonishing hero.

The second South Asian Victoria Cross winner belonged to the unit on the Patcham Down Memorial with the most deaths. The 39th Garwhal Rifles lists one Naik and five Riflemen. A Naik is similar to a Corporal. Darwan Singh Negi was hospitalized at the Brighton Royal Pavilion but he didn’t die. Of the six memorialized names in the unit, which you can see in the photo above, three have the name of Negi.

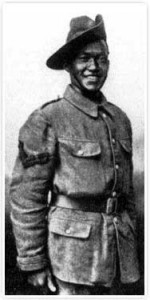

Darwan Singh Negi received his Victoria Cross from King George V on the same day as Khan for an action that happened about a month later. He was in Festubert in what would become the Battle of Artois. He and his fellow soldiers needed to retake trenches that had been seized by Germans. So they stood at the top of the trenches on either side, threw in bombs, and then jumped in themselves and bayonetted their way back into possession of each trench. They did this all night long until they had retaken all of the trenches. Negi, a Sikh, was especially skillful at this technique of hand-to-hand combat. During the Victoria Cross ceremony, King George V asked him, “What can I do for you?” Negi said his home area in India needed a middle school and the King had one built.

Nepal recently suffered a devastating earthquake and a major aftershock, so let’s honor their WWI Victoria Cross hero, Kulbir Thapa. He’s not on the Patcham Down Memorial but his last name is represented by three men. Thapa was injured September 25, 1915 in a battle near Fauquissart, France. In the melee, he found a wounded British solider who was not even in Thapa’s unit. Despite being injured and encouraged to save himself, Thapa stayed with the soldier for 24 hours and finally was able to drag him to a place of relative safety. Then he went back twice to save two South Asian soldiers. He went back into the fight once more to get the British soldier to full safety. These are roundtrips. So Thapa ran into a raging battle seven times in order to save these three soldiers.

I made my donation to the victims of the Nepal earthquake via Shelterbox. In one precisely packed box, they provide a tent big enough for a large family, along with blankets, mosquito netting, a stove with cooking equipment, water containers with filtration, a tool kit, warm hats & gloves, and a children’s activity pack. The tents are especially needed in Nepal as their monsoon season begins.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Peter Francis of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission for assistance with some details in this article and for providing two photos.

Photo Credits

© Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Patcham Down Indian Forces Cremation Memorial (1) with Chattri Memorial and (2) during construction

Wikimedia Commons: Royal Pavilion, Khudadad Khan, Darwan Singh Negi, and Kulbir Thapa

Follow

Follow