Titanic’s Musicians

(Along with Titanic’s 100th anniversary, today is my grandfather’s 110th birthday. I don’t know how much the Titanic news effected California’s Italian immigrant population, but my great-grandparents must have spent some time that day thinking about their own Atlantic voyage in the previous century.)

Titanic’s musicians hold the most honored position in its many tales of heroism. Shortly after the iceberg hit, the band started playing cheerful tunes. They kept on playing during the crisis, right up to their final “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as the ship submerged.

As with most legends, some details are controversial. Did they take a break? It looks like they did, since they seem to have acquired lifejackets in the second half of the concert. Also Bandmaster Wallace Hartley’s pockets were found filled with small valuables, which he might have grabbed in his cabin when he retrieved his lifejacket. The biggest music controversy is the last song. Was it really “Nearer, My God, to Thee” or perhaps “Songe d’Automne?” Each has its supporters, with carefully constructed and convincing scenarios.

More important is the heroism of these men as they helped passengers endure disaster. Hartley once told a friend, “When men are called to face death suddenly, music is far more effective in cheering them on than all the firearms in creation.” He proved this on the Titanic and his valor soothed two nations.

With the eight musicians hailed as the finest examples of manhood, as many as 40,000 attended Hartley’s funeral procession in Colne, Lancashire. The parade had eight bands, one choir, and even a second line of mourners, about as close to a New Orleans jazz funeral as Edwardian England could get. The Titanic Band Memorial Concert at the Royal Albert Hall included seven orchestras, with such prominent conductors as Edward Elgar and Thomas Beecham.

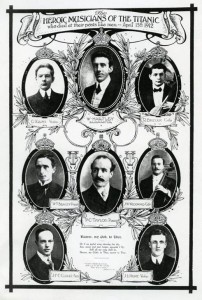

The band inspired at least 18 group and individual memorials. Several of them seem to have been based on a poster produced by the Amalgamated Musicians Union (AMU) of Southampton, which sold 80,000 copies in the first few months. Proceeds were contributed to a musicians’ convalescent hospital.

Titanic’s band was actually two bands, a Quintet for the First Class dining room and a Trio for the Parisian Café. Here’s the lineup, suggested by Titanic experts Walter Lord and Jack Kopstein:

Quintet

Wallace Hartley, Bandmaster and Violin

Theodore Ronald Brailey, Piano

John Frederick Preston Clarke, Bass

John Law Hume, Violin

John Wesley Woodward, Cello

Trio

Percy Cornelius Taylor, Piano and Cello, possible Trio Leader

Roger Marie Bricoux, Cello

Georges Alexandre Krins, Violin

The AMU poster includes eight photos with two large ones in the center column and three on either side. One of the larger photos is Bandmaster Hartley, the other is Taylor. None of my resources comment on Taylor as Trio Leader, however I assume the AMU thought he functioned in that position. The instrumentation suggests he was in the Trio and his photo is enlarged in the poster. The two side columns are headed by Krins and Bricaux, both Trio members identified by Lord, with the four Quintet members below. This suggests the poster was organized to show the two different bands.

If my analysis is correct, then the AMU missed an opportunity. The band leaders are arranged as Quintet and Trio because Bandmaster Hartley has to be at the top. But the rest are organized as Trio and Quintet. If the Trio members had been placed at the bottom, then the Quintet would have been next to Hartley and the Trio next to Taylor.

This error became more prominent when the arrangement was used for the Titanic Musicians’ Memorial in Southampton, where the AMU was headquartered. Here the names surround a carving of the Titanic being held by a deity. It feels like a circle, which can give the appearance of equality while maintaining hierarchy, as we saw in the Shuttle Challenger Memorial at Arlington. Hartley is at top and Taylor, bottom, both in larger letters. The remaining musicians on either side are in the same arrangement as the poster, with the Trio on top and the Quintet below. So the two leaders are again separated from their respective bands.

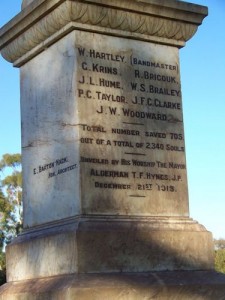

The Titanic Bandsmen Memorial in Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia, may have used the AMU poster as a starting point and then gone off in its own direction. This memorial is a broken column, symbolizing young lives cut short. Here the two Trio members are immediately after Hartley, in the same order as the poster although Bricoux’s name is misspelled. They are followed by the Quintet in a different arrangement from the poster, with possible Trio Leader Taylor among them.

Recently commentators have argued that the band may have cost lives, that its music lulled passengers into a false sense of security. At the beginning some passengers may have felt safer on the ship with its cheery music, perhaps one reason lifeboats launched half full. Yet while the music played, passengers remained relatively courteous, at least in First Class. We have their stories because they are the ones who survived. People calmly sacrificed their own lives to save others, including Miss Edith Corse Evans who gave her place on the last collapsible boat to a mother of five. When the music stopped, things started getting mean on the lifeboats. On the ship, Wallace Hartley and his Trio and Quintet had kept passengers calm as they sorted out who would live and who would die. Then the musicians comforted two nations in mourning with the story of their selfless attention to duty.

Primary resource for this article is Steve Turner’s The Band that Played On: The Extraordinary Story of the 8 Musicians Who Went Down with the Titanic.

Illustration credits: Wallace Hartley; Amalgamated Musicians Union Poster (April 12, 2012); Titanic Musicians Memorial in Southampton; Titanic Musicians’ Memorial, New South Wales, Australia; New South Wales Memorial Detail

Follow

Follow