Alice Koenigswarter Halphen and the Rue des Deux Ponts

(This post honors my father, Jack Bertolucci, who served in the Pacific during World War II. He died last year. Today would have been his 89th birthday.)

Memorial Plaque at #8 rue des Deux Ponts, Paris

The Ile-St-Louis, a wealthy residential area in central Paris, appears today much as it did in the 17th Century, except for the even numbered side of rue des Deux Ponts, which was gutted between 1912 and 1930 to widen the street. Taking advantage of that opportunity, Alice Koenisgswarter Halphen built low-income housing for large Jewish families in the 08-12 block. The project was sponsored by her Foundation Fernand Halphen, named after her husband, a wealthy composer who died in World War I.

The families lived there until September, 1942 when Nazis captured the residents and transported them to Auschwitz, where they all died. After the war, the complex remained low-income housing, sometimes for relatives of the original families. A plaque was installed, “In memory of 112 inhabitants of this house with 40 small children, deported and died in the German camps in 1942.” Another 2007 plaque lists the names of inhabitants who died at Auschwitz. It mostly gives surnames, in alphabetical order except for the last one. Parents are indicated by “M Mme,” with 66 children under age 21 primarily shown by number. The largest families were “M Mme ADONER et 5 enfants” and “Mme Veuve WIOREK et 6 enfants.” In 2004, new developers tore off a mosaic entrance plaque with the words “Foundation Fernand Halphen 1926.” Low-income housing became luxury apartments.

Alice Halphen experienced another aspect of Nazi occupation in 1940 when they stole art from her lavish chateau in Chantilly. According to her son Georges, he and his mother survived the war on a farm. Georges eventually joined the Resistance. After the war, Mme Halphen wrote a timeline article about the Jewish experience in occupied France.* It is perhaps not a coincidence that her low-income housing became high rent the year after her son’s death in 2003.

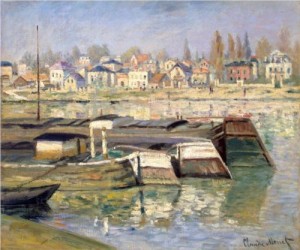

The Seine at Asnières by Claude Monet

One piece of art stolen from Alice Halphen was Monet’s The Seine at Asnières. Its provenance got altered via a trip to Switzerland. In 1948 the Detroit Institute of Arts bought it from a reputable dealer. About a year later, another art dealer contacted the DIA asking if the painting was the same one he sold to Mme Halphen and providing proof of her ownership. So in 1950, the DIA became the first museum to return Nazi stolen art to its rightful owner.

The DIA itself is now in danger of losing its collection. Acquired during times of prosperity, its art is being eyed by creditors as a source of repayment. To keep the collection in Detroit, a “grand bargain” was proposed that would privatize the museum, which would buy the art from the city. The money would be used for employee pensions. It’s a popular idea that has garnered large donations from prominent foundations and from the auto industry. But it may not be legal because it prioritizes one group of creditors (pensioners) over another (bond holders).

Alice Halphen served her community by providing a place for people in need to live. The contributors to the DIA, of art and funding, serve their community by providing beauty and culture. The bond holders also served their community. When Detroit asked for a loan, they provided it. Today, June 20, Governor Rick Snyder signed a bill allowing the state to contribute $195 million to the “grand bargain.” In the meantime, pensioners, who expected a secure retirement, have until July 11 to vote on the deal, but these are just the first steps in what may be a long story with a lot of protagonists.

* “Lest We Forget . . . ” by Alice Fernand-Halphen appeared in the December 1948 issue of The Jewish Monthly. My thanks to Elliott Wrenn of the U S Holocaust Museum for sending me a PDF of this article.

Credits: Memorial Plaque at #8 rue des Deux Ponts, Paris; The Seine at Asnières by Claude Monet

Follow

Follow