Arranging to Persuade: Tunneling or Guided Persuasion

Fogg’s Principle of Tunneling: “Using computing technology to guide users through a process or experience provides opportunities to persuade along the way.”

This month we take a journey to tunneling in our series on B. J. Fogg’s seven tools of persuasion from his book Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Fogg cites software installation as a tunnel. That frequently involves staying near the computer and answering questions every so often. You are a captive audience as the installation proceeds. As such, you may experience promotions for other products or about the benefits of your new purchase. You and the company share a journey of software installation, with the company selecting the sights along the route.

In his narrative, but not in his Principle, Fogg defines a tunnel as a committed journey, like an amusement park ride. Once you sit in that gondola (or begin software installation), you’re committed to the entire journey. In information arrangement, tunneling encompasses a wider definition. You are enticed along a journey that you may or may not complete. At any point you may decide what you are looking for is not worth the effort, or you may complete the journey, ending it only when you find what you are looking for.

One example of persuasive tunneling is the arrangement of a grocery store. Many people pop into the store just for a quart of milk. Milk sometimes goes bad suddenly so you pick it up on a quick errand. That’s why milk is always at the back of the store. If it was at the front, you would buy that one item and head on home. When it’s at the back, you travel through the store aisles, experiencing other products and perhaps buying something else.

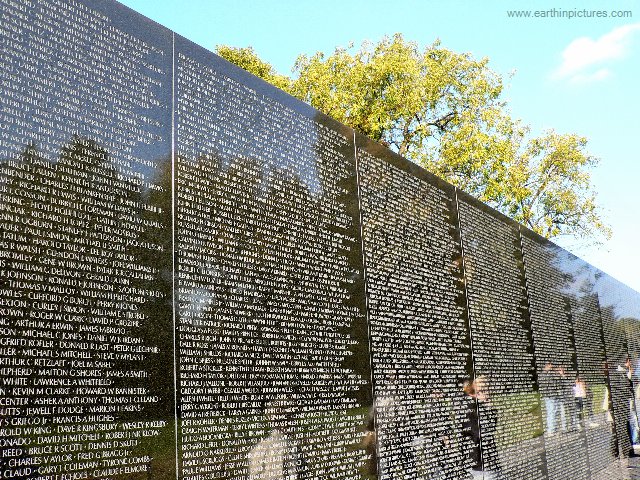

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial (VVM) provides a more complex tunnel. Its 140 panels increase in height from 8 inches at the ends to over 10 feet in the center. Names are inscribed in chronological order by date of casualty and alphabetical order within each day. So it would seem that visitors take a journey from the beginning of the war to the end.

That is the case, but the journey actually begins in the center. Maya Lin wanted the VVM to symbolize a circle so the names begin and end at the tall center panels, indicated by the only two dates on the Memorial, 1959 and 1975. No other dates appear. Walking along the panels, the only indication of a new day is the beginning of a new set of names in alphabetical order. Even though this is the journey of the Vietnam War, it does not feel like a persuasive tunnel, since we only see a massive display of names.

Many visitors believe the chronology begins at the short left panel. That’s logical since we read from left to right, not from the center to the right to the left and back again to the center. When we experience the VVM from left to right, the shape of the memorial helps us feel the shape of war. A few deaths at the beginning, building to a crescendo at the center and winding down to just a few names at the end. In this case, because we know the names are in chronological order, the shape of the VVM creates a journey along the panels, persuading us to experience feelings about the progression of war.

Illustration used with permission from Microsoft.

Follow

Follow